250-32160 South Fraser Way

Abbotsford, B.C., V2T 1W5 Canada

Abbotsford, B.C., V2T 1W5 Canada

Stay In Touch

Join our email list and we’ll keep you

posted on the latest BC Egg news

Water goes through a filtration system so that the quality can be monitored easily. Vitamins and occasionally vaccines can also be added to the water system to ensure every bird receives a boost.

Hens have access to nutritious feed on a regular schedule. Bird weight and feed consumption are both monitored to ensure the hens aren’t eating too much or too little.

There are sensors in the barn to monitor air quality, and to alert the farmer if there are any problems. Barns have ventilation systems to keep fresh air flowing through and to keep dust levels under control.

Barn temperature is always monitored to make sure the hens are cozy when it’s cold and don’t overheat when it’s hot. Hens generate a lot of heat themselves, so cooling and ventilation are particularly important. Many barns have a water-cooled radiator pad on the side of the barn that cools the air as it flows over and moves into the barn. Fans or “tunnel venting” then pull the cool air through the entire barn to keep the hens comfortable.

What goes in, must come out, and managing all the poop hens produce is an important part of keeping them healthy and the eggs clean. Each barn style has a different way of keeping the manure away from the hens, collecting it, keeping it dry, and moving it out of the barn. Chicken manure is a fantastic fertilizer so once it’s collected from the barn, it’s often used by crop or produce farmers. Fun fact: organic hens will produce organic manure!

Hens like to live in groups, called flocks, so it’s natural for them to cluster together whether they’re in a barn or out in a field. To ensure they still have room to exhibit their natural behaviours, the amount of space they have is regulated and barns and enriched housing all have limits on the numbers of birds that can be housed based on the barn area. Even outside space is regulated, and a minimum requirement of space per bird must be met for free range and organic fields.

Perching – Enriched and cage-free housing systems have perches for the hens, so they can roost and rest naturally. Hens like to curl their feet around a perch, so they find perching relaxing.

Scratching – Hens like to scratch at the ground so most housing types include an area or scratch pad to encourage hens to scratch and peck.

Dustbathing – Hens dust bathe to control excess oil in their feathers and skin. Dust bathing helps keep their feathers clean and can also help smother mites or parasites that can cause skin irritation. Most cage-free housing styles offer hens the opportunity to practice this natural behaviour.

Nesting – Hens like to nest to lay their eggs somewhere private, dark and sheltered. Their housing systems have nest boxes which are separated from other areas by a curtain to keep the box darker and more secluded. The floor of the nest box is sloped slightly, so that when the eggs are laid, they roll gently to the back of the box and onto a conveyor system that then takes the eggs through the barn to an egg collection room.

Conventional cages have been the most common form of housing for years. They keep the birds safe, give them access to food and water and house them in small groups. The cages have a wire floor so the manure can be kept away from the birds, helping to keep eggs clean and birds healthy. They are a very efficient use of space, meaning that not a lot of land is required for an egg farm and that helps keep the cost of eggs produced in this system very affordable. However, this housing system limits the movement of the birds and doesn’t let them express all of their natural behaviours.

Enriched housing is the new standard for egg laying hens in Canada. This housing system lets hens live in small flocks or “colonies” with much more room per bird than conventional cages.

Enriched housing is furnished with different amenities for the hens to help keep them comfortable and to allow them to practice their natural behaviours. There are scratch pads for scratching and pecking, perches so the birds can perch to rest, and nest boxes so they have somewhere sheltered and secluded to lay their eggs. Manure is easily managed through a belt system that keeps it away from the hens and moves it out of the barn regularly.

In addition, each colony group can be inspected separately, allowing farmers to pinpoint signs of distress or illness more easily and to address these issues before they spread to the entire flock. Because this system is such an efficient use of space and is an effective way to manage feed, water, manure and egg collection it helps produce more economical eggs, giving consumers one of their most affordable egg options at the grocery store.

Free run housing doesn’t confine the hens at all – they are loose in the barn and can roam where they please. Barns may have slatted floors where the manure can fall through, keeping it separate from the hens, or have floors with litter allowing the hens the opportunity to dustbathe. Perches run throughout the barn, as do feed and water lines, so the hens can eat, drink and rest where they like. Nest boxes are placed in a line down the centre of the barn (or in rows running the length of the barn) and much like in enriched housing, they have slightly sloped floors so the eggs roll out the back, and on to a covered conveyor belt so they can be moved to the front of the barn and into the egg collection room.

Some free-run barns have “aviary systems” within them – a multi-tiered “jungle gym” apparatus that allows the hens to explore different levels. Aviary systems have perches, nest boxes and food and water on different levels to encourage the hens to move between levels. This system also has the benefit that hens can perch up high which they especially like to do at night when they sleep.

Free-range housing looks much like free-run housing with one large difference – the hens are also allowed outdoors onto a fenced range. The barns are the same as free run and just like free run may have an aviary system or birds may just be free to roam on the floor. They access the range outdoors through openings called “pop holes” and these doors must meet certain size and placement requirements to ensure all the birds can get outside easily. Once outdoors, the range must also meet specific quality standards and must have grassy areas as well as sheltered areas to provide shade and shelter from predators.

Food and water are kept in the barn, so it doesn’t attract pests or wild birds who might expose the hens to disease, and so the hens are encouraged to come indoors at night. Access to the outdoors can be limited if the weather is too hot, too cold or too wet for the birds – all situations where it wouldn’t be healthy for the hens to venture outside. However, hens must be guaranteed access to the outdoors for a certain minimum number of hours and days over the course of their lives. Hens also have to be trained for a few months before they go outdoors, so access to the range can be restricted until a flock is established in a barn and used to laying eggs in nest boxes.

Organic housing and care builds further on free-range housing. Hens are required to have more space per bird than free-range housing, both in the barn and out on the range, meaning that the land required for organic farms is more extensive than other housing types. Outdoor ranges must also be organic and can’t be treated with pesticides or herbicides. Plus, they have to have a buffer zone between them and any neighboring fields that aren’t organic, again adding to the amount of land required for this type of farm.

Birds are fed only certified organic feed and can never be given antibiotics. This doesn’t mean that they’re denied treatment if they get sick, but rather that they’ll lose their “organic” designation and become “free-range” hens if they are given antibiotic medication. Whenever any hen is given antibiotics, it’s done with veterinary supervision to address a specific illness and eggs from that hen or flock are removed until the antibiotics are cleared from the hen’s system, so eggs from our egg farmers will never have been exposed to antibiotics.

Organic farms also undergo an additional inspection from a third-party auditor to review their organic standards and certification.

Hen feed is produced by feed companies that employ poultry nutritionists who specialize in formulating a balanced, healthy diet for the birds. Farmers often work with feed companies and their poultry nutritionists to formulate feed specifically for each flock and can address health concerns in their birds by changing the feed formula. For example, if a farmer notices that their flock is producing eggs with weaker shells the hens may need more calcium, so the feed company will adjust the feed recipe accordingly. Hen feed can also help manage the size and quality of the eggs the hens produce. Protein-rich feed will typically help hens produce consistently sized large and extra-large eggs, while also keeping the hens feeling full longer so they don’t need to consume quite as much feed. Feed is also adjusted as the hens age, or as the seasons or weather changes. Farmers continually monitor how much their birds are eating and the average weight of the birds as both factors can be an indicator of overall hen health.

Hen feed provides a complete meal for our egg laying hens, with all the nutrients they need to be healthy and to produce nutritious eggs. Their feed includes corn, wheat, fats, soybean meal (for protein), minerals (often in the form of limestone and salt), as well as enzymes, amino acids and vitamins that improve digestibility and round out the nutrition profile. Many of these ingredients help “upcycle” food products that would be otherwise wasted: grains that are cracked or otherwise don’t make the grade for human use, wheat that has frost damage or has sprouted so it can’t be ground into flour, feed-grade corn, canola or soybean oil that isn’t high quality enough for human use, spent grains from breweries, the list goes on. While some of the ingredients in hen feed are brought in from outside of the province, most hen feed for our egg farms is milled right here in BC from one of a number of local feed companies.

For the most part, all eggs have the same nutritional value – it doesn’t matter if they’re free run, organic or conventional. However, there are two notable exceptions to this rule. Vitamin D or Omega 3 eggs are “enhanced” eggs with bolstered levels of Vitamin D or Omega 3 fatty acids. These enhanced eggs are achieved by feeding the hens a special diet. Vitamin D occurs naturally in eggs, but adding Vitamin D to the hen’s feed results in eggs with even higher Vitamin D levels. The addition of flax seed oil or fish oil to hen feed increases the levels of omega 3 fatty acids in eggs and makes them a good source of omega 3 for consumers.

Two things you won’t find in hen feed are hormones and steroids. While many consumers worry that these are added to poultry diets, and subsequently filter through to the eggs we eat, feeding hens hormones or steroids (or boosting the hens with additional hormones or steroids in any other way) has actually been banned in Canada since the 60s.

Antibiotics are a concern for many consumers but in egg farming they’re very rarely required. Medically important antibiotics are only used when there are no other options, and then only with veterinary supervision. If a hen receives treatment with antibiotics her eggs are removed from production for the duration of her treatment as well as for a recovery period afterwards, while the antibiotics are metabolized and flushed from her system. This way there’s never any risk of eggs becoming contaminated with residual antibiotics and passing on to humans.

Laying hens are raised from chicks that are hatched from fertilized eggs from “breeder” hens. The eggs are incubated in hatcheries and once hatched the female chicks are shipped to specialized “pullet growers” within just a few days. Currently, the male chicks that are hatched are humanely euthanized, but thanks to ongoing research hatcheries will soon be able to identify the sex of a chick before they hatch, so that embryos that will produce male chicks can be culled before the chick fully develops.

Once a chick is fully feathered, at about 2-3 weeks old, it becomes a “pullet.” Pullets are young hens that have not yet reached adulthood and started to lay eggs. They’re raised in barns designed for their use, but without nest boxes or the equipment to collect eggs. At about 19 weeks pullets are mature enough to start laying eggs and will become “hens.” They’ll be moved to their final homes in layer barns, furnished with nest boxes and depending on the type of farm, either enriched or free-run housing.

Laying hens often take a bit of time to learn to lay their eggs in nest boxes, since they don’t have nest boxes as pullets. Often farmers will find eggs on the floor of the barn until hens get used to nesting in the new nest boxes. Farmers with free-range and organic hens will keep their new hens indoors for several weeks until they are settled in the new barn and used to laying before they are allowed outdoors onto the range. Hens will reach their peak laying potential at about 26 weeks old. They’ll then lay almost an egg a day until they start to slow down at about 64 weeks.

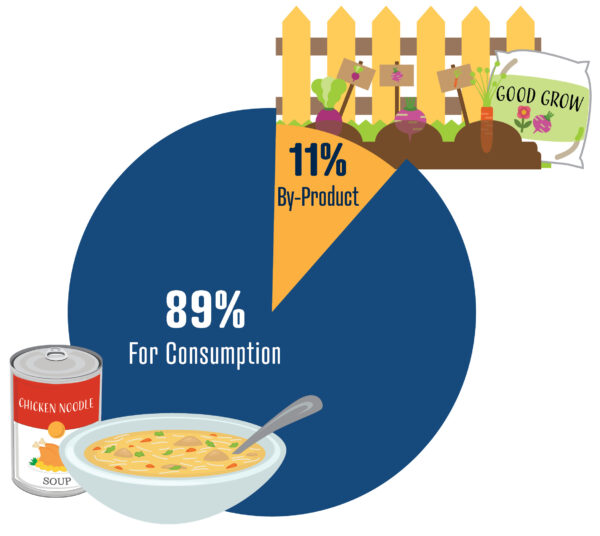

When hens reach about 72 weeks of age, they’re at the end of their laying cycle. Specialized crews will come to a farm to catch the hens, and then the hens will be humanely euthanized and sent to a processing plant. There, all parts of the hen are used in food products like chicken noodle soup, pet food, and bone or blood meal for garden fertilizer. No part of the hen is wasted, and even the manure from the barns is used as fertilizer for crops and produce.